air handling units books

Find out how to access preview-only content ChapterArtificial Intelligence and Soft Computing Volume 6113 of the series Lecture Notes in Computer Science pp 58-65Fault Diagnosis of an Air-Handling Unit System Using a Dynamic Fuzzy-Neural Approach * Final gross prices may vary according to local VAT. This paper presents a diagnostic tool to be used to assist building automation systems for sensor heath monitoring and fault diagnosis of an Air-Handling Unit (AHU). The tool employs fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) strategy based on an Efficient Adaptive Fuzzy Neural Network (EAFNN) method. EAFNN is a Takagi-Sugeno-Kang (TSK) type fuzzy model which is functionally equivalent to the Ellipsoidal Basis Function (EBF) neural network neurons. An EAFNN uses the combined pruning algorithm where both Error Reduction Ratio (ERR) method and a modified Optimal Brain Surgeon (OBS) technology are used to remove the unneeded hidden units. Simulation works show the proposed diagnosis algorithm is very efficient which can not only reduce the complexity of the network but also accelerate the learning speed.

Share this content on Facebook Share this content on Twitter Share this content on LinkedIn

hotel heating and cooling room units Fault Diagnosis of an Air-Handling Unit System Using a Dynamic Fuzzy-Neural Approach

running an ac unit inside Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing

how to measure for an ac unit 10th International Conference, ICAISC 2010, Zakopane, Poland, June 13-17, 2010, Part I Lecture Notes in Computer Science Artificial Intelligence (incl. Robotics) Information Systems Applications (incl. Internet) Computation by Abstract Devices Information Storage and Retrieval Algorithm Analysis and Problem ComplexityThis part of the Energy Efficiency Manual shows you how to save energy in induction air handling systems.

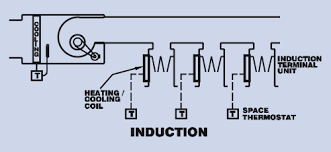

Induction systems are a form of single-duct reheat system, which is notoriously wasteful because it uses heating energy to warm up air that has been previously cooled. During low-load conditions, much more energy may be cancelled by reheat than actually enters the space to provide cooling or heating. The primary air is cooled by a coil in the air handling unit. The temperature in individual spaces is regulated by a reheat coil in the terminal unit, which is controlled by the space thermostat. The high pressure requirement increases fan power, even though the central fan delivers less volume. Also, induction systems are designed to operate with low primary air temperatures. This may require lower chilled water temperatures, which reduces the efficiency of the chiller. The most visible distinguishing feature of an induction system is the terminal unit. Induction terminal units have no fans. Air movement through coils in the terminal unit is induced by high-pressure air, called “primary” air, that comes from a central air handling unit.

The primary air is passed through an array of nozzles in the terminal unit that create a venturi effect, or vacuum. The vacuum recirculates air from the space through the terminal unit coil. The space air, called “secondary air,” mixes with the primary air and is discharged into the space. Induction terminal units commonly are packaged in enclosures that are similar in size and appearance to fan-coil units. They may also be installed in ceiling plenums. The coils are almost always hydronic. The temperature of the coil may be controlled by throttling the water through the coil, or a damper may be installed in the terminal unit to bypass air around the coil. If the terminal unit coils are designed to change between heating and cooling, the system will have much less reheat energy waste than if the coils are designed only for heating. When the space requires cooling, both the coil in the air handling unit and the coils in the terminal units cool the air. Reheat does not occur under these circumstances.

However, when a space requires heating, the coil in the terminal unit must cancel the cooling energy in the primary air. The amount of reheating that is unavoidable depends on the diversity of the space loads. If some spaces have a high cooling load at the same time that other spaces have a heating load, reheating of the primary air will occur in the spaces that require heating. Terminal units that have changeover coils require effective drainage of the moisture that condenses on the coils during cooling operation. The design of an induction system with changeover terminal unit coils may assume that dehumidification is accomplished by the coil in the air handling unit, rather than by the coil in the terminal unit. However, conditions can still occur that cause moisture to condense on the coils. The energy conservation measures presented here include the methods for avoiding excess reheat, which can be done with inexpensive temperature reset controls and other methods. You will learn to apply temperature setback to induction systems, along with techniques for maintaining air distribution efficiency.

100 Years, 100 Buildings My recent posts at World-Architects Blair Kamin's article of December 5th, "Doctored photo raises questions about ethics in architecture contests," is like one of those catchy, yet slightly annoying pop songs – it has stayed with me for the last week and a half, even though I have issues with his conclusion. The main point of the article is that architects and architectural photographers should honestly portray buildings that are being judged for awards on the basis of those photos. An AIA Chicago Award given to JGMA's El Centro project was the basis for Kamin's critique. The building is striking for the way it curves to follow the Kennedy Expressway and articulates the facade with angled fins that are blue on one side and yellow on the other. It's as if the building was designed to please the motorists zipping by on the expressway. With this in mind, it's obvious to know which of these two photos from the article is the doctored one and why it was:

Yes, those rooftop mechanical units are an eyesore that are magically missing from photographer Tom Rossiter's photograph that was part of the awards submission. Rossiter removed them with Photoshop, though it's not clear from Kamin's article if he did it at the urging of the architect, Juan Moreno, or not. What is clear, based on the quotes of jury members that Kamin contacted for the article, is that the editing went too far – far enough that the building might not have received the award if the view was represented truthfully. Now, I agree that this Photoshop manipulation went too far, but I don't agree that the building would not have been deserving to win an award because of this manipulation. Take the fact that Kamin's own 2014 review of the building, which he obviously saw firsthand, did not initially include mention of the air-handling units; they were brought to his attention by a reader and included only in the online article. This says to me two things: 1) those units are not (as) evident close to the building;

and 2) our brains don't pay attention to those units when seeing the building from the Kennedy. In regards to #1, I have visited the building and can attest to that. Although I don't have access to the photos I took of it, here is a Google Street View of the contested elevation seen from the frontage road next to the Kennedy: The units poke above the roof slightly, hardly attracting attention to themselves, and therefore easily overlooked by architecture critics. In regards to #2, on a number of occasions I have seen the building from the Kennedy, and while, again, I don't have access to any of my own photos, this is where having a photo doesn't help. On each instance that I zipped by the building – be it driving downtown or in the other direction, be it as the driver or as a passenger – I either didn't notice the units or they did not plant themselves in my memory in any lasting way. This is not a personal defect; this is linked to how our brains work and how the building is designed.

The human brain does not process and therefore memorize everything we see; instead it is focused on a very narrow realm in the center of our field of vision (somewhere I read a 15-degree cone). In the case of driving by El Centro – something that lasts about 5 to 20 seconds, from what I recall – my attention was always focused on the angled fins. How couldn't that be the case, given their colors and the way they change on passing? So here is a case where the building's positive attributes need to be experienced to be appreciated. An honest photographic representation does not capture the experience, because instead of the cars zipping by, as in Rossiter's doctored photo, we are zipping by, which changes everything. What Moreno and Rossiter should have done to maintain their honesty and integrety, given the assumption that the jurors would not know the building firsthand and would be basing their judgments on photographs, was to carefully choose the (honest) photographs that capture the building's good qualities and play down its bad ones.

A photo from the frontage road would capture this elevation and its relationship to the road as well as a view from across the Kennedy. Architects and photographers are selective in their views all the time. Take the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, near where I live. The top photo is from architect Thomas Leeser's website and the bottom one was taken by me on the way to work this morning: A few steps closer and the angle of the facade omits the rooftop units – no Photoshop necessary. Ultimately, the point with dissecting the JGMA building and, to a lesser extent, the Leeser building, is not about representation, but about design and the role of mechanical engineering. Do all buildings need such large rooftop units? Can buildings be designed in a way that the size of the units is reduced and their placement reduces the impact on a building's exterior appearance? I know it's not easy to deal with these and other units (rooftop screens are often the first thing to go in value engineering, for example), but it should be the goal of every architect to design buildings that are not marred by the mechanical engineer's contributions.